Albert L. Gordon dies at 94; attorney fought for gay

rights

A heterosexual whose twin sons were gay, he battled

bigotry in law enforcement and successfully argued for

the revocation of laws against consensual homosexual

acts.

By Elaine Woo

September 6, 2009

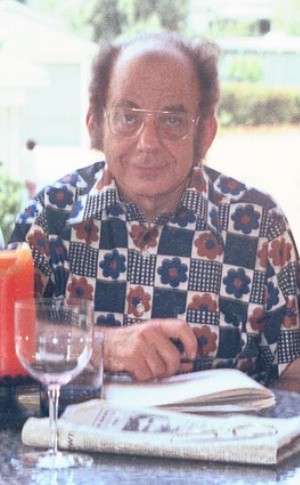

Albert L. Gordon, an attorney who helped advance gay

rights in the 1970s and '80s by challenging

discriminatory practices and laws, including a

successful effort to decriminalize consensual

homosexual acts, died Aug. 10 in Los Angeles. He was

94.

He died of natural causes, his son Harold said.

Gordon, a heterosexual whose twin sons were gay,

became a lawyer in his late 40s and devoted most of

his practice to defending the rights of homosexuals

and battling the bigotry of law enforcement. Often

working for free, he became known as "the leading

pro bono lawyer to L.A.'s gay community," historians

Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons wrote in their

2006 book "Gay L.A."

"Before there was a straight-gay alliance in

America, there was Al Gordon," the Rev. Troy Perry,

a longtime activist and founder of the gay-friendly

Metropolitan Community Churches, said in an

interview last week. "When other people wouldn't

touch us, he did. He was a hero."

One of Gordon's most memorable cases stemmed from a

notorious raid on a gay bathhouse on Melrose Avenue

in 1975, when scores of Los Angeles police officers

broke up a mock slave auction staged as part of the

entertainment for a gay community fundraiser.

Apparently not amused by the gimmick, the police

treated the event as actual human slave trafficking,

a felony, and arrested 40 participants. Gordon

helped win their release.

He supported a second mock auction, organized by

Perry to raise defense funds, by going on the

auction block himself. He went for $369 to his wife,

Lorraine.

He also represented gay activists in another cause

celebre: a 10-year battle to force Barney's Beanery,

a popular West Hollywood restaurant, to remove an

offensive sign. The misspelled sign, "Fagots Stay

Out," was taken down in 1984.

Born in Pittsburgh on May 29, 1915, Gordon moved to

California with his parents when he was an infant.

He attended Los Angeles City College, where he met

Lorraine. They were married in 1937 and their twin

boys, Harold and Gerald, were born later that year.

Lorraine died in 1987 and Gerald died in 1996. In

addition to Harold, Gordon is survived by his second

wife, Pearl.

During World War II, Gordon worked as an efficiency

engineer at Lockheed but was fired because of his

pro-union activities, Harold Gordon said. He

subsequently started a janitorial service, which he

ran with his first wife for about 15 years.

At the urging of a friend, he enrolled at the San

Fernando Valley College of Law. He passed the bar in

1962 when he was 47.

While Gordon was in law school, Gerald was arrested

for soliciting a vice officer. "My whole world just

fell apart," Gordon told The Times in 1974. "I'd

always had the normal stereotype of a homosexual as

a child molester or somebody effeminate. When my own

son was arrested, I just couldn't believe it was

true because he was neither of those things."

Gordon and his wife separated under the strain

caused by the arrest, and he was on shaky terms with

his son for several years."He was homophobic,"

Harold, who later came out as gay, said of his

father in an interview last week.

What softened Gordon's attitudes toward homosexuals

was getting to know several of Gerald's gay friends

when they came to him for legal advice. One night he

summoned the courage to ask his son if he was gay.

When Gerald answered yes, Gordon broke down and

asked his outcast son to forgive him.

"I was the one who changed," Gordon recalled in the

1974 interview.

That year he joined with gay liberation leader

Morris Kight to devise a challenge to the 1915

California law that made oral sex a felony. They

recruited a gay male couple, a lesbian couple and a

heterosexual couple to sign affidavits stating that

they had broken the statute against oral copulation.

Gordon then informed the LAPD that the "felons"

would present themselves for arrest at the Los

Angeles Press Club. As he expected, no police showed

up but a media circus ensued, guaranteeing coverage

of a law he regarded as hypocritical.

"He loved antics. He liked to really stir things up

and fight for the little guy," said Los Angeles

lawyer Thomas F. Coleman, who was a UCLA law student

when he began working on gay rights issues with

Gordon in the early 1970s.

Undeterred by the absence of police, Kight made a

citizen's arrest and drove the three couples to the

Rampart police station, but the station commander

refused to bite.

The next stop brought the offenders no closer to

jail. At the office of the assistant district

attorney, they were told no charges would be pressed

because prosecuting private sexual acts between

consenting adults was against the district

attorney's policy.

Armed with this statement, Gordon and Kight argued

that the state penal code was misleading and should

be changed. In 1975, the state Legislature agreed by

revoking the laws against consensual homosexual

acts. The change removed a major tool of police

harassment of gays.

"He helped change the legal system in California,

particularly in Los Angeles," Coleman said. "The gay

and lesbian community really owes him a debt of

gratitude."

|